When it comes to discriminating against women, you’d think that only sexist organizations would be involved. But did you ever imagine that meritocracies would encourage managers to discriminate against women?

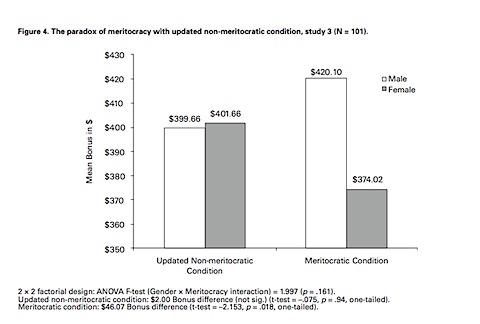

Research conducted by Emilio Castilla and Stephen Benard, published last year in Administrative Science Quarterly, documents a disturbing dynamic that the authors call “The Paradox Of Meritocracy”. In their rigorous set of empirical studies, they found that

Although these meritocratic organizations aren’t explicitly encouraging managers to discriminate, they seem to be inadvertently freeing managers to demonstrate gender bias when they award raises and bonuses.

This discovery is distressing. The Paradox of Meritocracy casts doubt on a range of efforts that organizations are using to try to reduce gender discrimination.

Meritocracies and Why We Love Them

We love meritocracies. We love the idea that organizations will link members’ career success to their actual performance. We love meritocracies because we think that merit is the fairest, most objective way to reward some people (meritorious ones) over others. After all, meritocracies explicitly reject the idea that a member’s gender, race, sexual orientation, age, or other social category should influence how that member is evaluated and rewarded.

Managers, leaders and HR experts especially love meritocracies. They enthusiastically advocate for merit-based systems because they believe that tying rewards to performance evaluation motivates people to work harder. Not only that, but linking merit and pay also increases employees’ satisfaction with their work-reward ratio and with the organization itself.

Linking Organizational Rewards to Individual Merit

As organizations have tried to increase fairness and decrease discrimination, they have emphasized practices that create a formal link between evidence-based performance evaluations and promotions / pay increases.

One strategy has been to shift to ‘pay for performance’, where there is an explicit link between performance rating and pay increases. A second strategy has been to decouple the performance evaluation conversation from the salary decision, so that a manager is not unintentionally thinking about both of these when considering a candidate.

Unfortunately, merit-based rewards in organizations don’t seem to do what we’ve hoped.

Merit Pay Does Not Reduce Gender-based Pay Discrimination.

Despite the intent behind them, there is a consistent problem with merit-based practices: Women and minority men in the same organization, in the same job, and with the same supervisor, are found to receive lower salary increases than white men, even after same performance evaluation score (Castilla 2008).

Let me repeat that: It has been empirically demonstrated that:

Women and minority men in the same organization, in the same job, and with the same supervisor, received lower salary increases than white men, even after same scores on their performance evaluations (Castilla 2008).

Research on merit-based pay practices has consistently demonstrated that merit-based practices do not achieve gender- or race-neutral outcomes.

Is it the practices themselves, or something else that allows for bias? In their research, Castilla and Benard shifted focus to consider the role of organizational context. They aimed to compare what happens in organizations that strive to be meritocratic versus those that do not.

Most people would expect that organizations that strive to be meritocratic would do better at reducing gender-based pay gaps. But what Castilla and Benard discovered was exactly the opposite.

Highlighting the organization’s commitment to being meritocratic actually made gender-based pay discrimination worse.

The question is — why? Why do these merit oriented practices, meant to increase fairness, end up increasing discrimination?

The Role of The Organization in Supporting Biased Actions by Individuals

Castilla and Banard propose that there is something about the organization’s intent to focus on merit that leads organization members not to focus on merit. Their interpretation is, essentially, that when people are primed or reminded to feel unbiased, fair or objective by the organization itself, they feel freed to express the bias that they personally hold.

Castilla and Benard propose that one mechanism that explains the paradox of meritocracy is “moral credentials”. When people have established their moral credential as an unbiased person, they are more prone to express biased attitudes. It’s as though they’ve already proven to themselves – and others- that they aren’t unbiased. However, when these supposedly unbiased people act, they reveal real bias and discriminate against others. (Monin & Miller, 2001)

In addition to the straightforward credentialing mechanism that Castilla & Benard suggest, there are two other mechanisms that work in similar ways that also might be letting managers feel free to express bias in their decisions.

Moral Credentialing by Association

The ‘My Best Friend is X’ Effect. We know that individuals often feel that they have achieved their ‘I’m not prejudiced‘ bona fides by claiming to have relationships with the (potential) target group of discrimination. Some individuals even claim that they are not discriminatory (e.g., not racist, not sexist) because they obviously have a close association with specific members of the target group.

I like to call this the “My Best Friend is X” effect, after the most common statement people make to claim Moral Credential by Association.

We give ourselves moral credentials for being unbiased not only through actual relationships with others, but also through vicarious relationships with others. A study just published by Maryam Kouchaki demonstrates that individuals license or credential themselves vicariously, through identification with others who have “established non-prejudiced credentials”. Both the mechanism of association and the mechanism of identification might give managers the cover of moral credentials.

Do Organizations Provide Managers with “Vicarious Moral Credentialing”?

The idea of moral credentials influencing behavior has previously only been discussed as an individual phenomenon– something that a person does for him- or herself.

What’s new with the Paradox of Meritocracy studies is the idea that the organization itself can provide a halo of moral credentials for its managers.

The managers don’t need to think of themselves as being unbiased — they just have to think of their organization as unbiased or meritocratic. Then, the organization creates a halo for managers through three slightly different but distinct psychological tricks, when managers can:

- Think of their organization as being meritocratic and thus assume that bias has already been removed,

- Think that they are meritocratic because they are part of an organization that is meritocratic, and

- Think that they are like their organization, so that if it’s meritocratic, so are they.

In all three cases, managers no longer have any motivation to avoid applying biased stereotypes or to monitor their own expressions of bias. They are off the hook.

What can organizations do about the paradox of meritocracy?

Castilla and Benard suggest that organizations can try to counter the paradoxical dynamics of meritocracy by (1) increasing transparency around evaluations and salaries, (2) by increasing accountability, and (3) by reducing managerial discretion. While I’m not a fan of reducing discretion, it makes sense to have managers be more accountable for their decisions about other people’s merit and the appropriate award for that merit.

1. Organizations should report out historical patterns of evaluation and pay increase data, for each individual manager.

Managers need to become more accountable for knowing and monitoring their own personal patterns of behavior regarding evaluating and rewarding others. Organizations can help individuals to hold themselves accountable by providing each manager with an historical summary and analysis of pay and evaluation decisions, broken out by gender, race and other diversity criteria of the persons evaluated. This way, managers can see their decisions over time, and note whether their pattern of behavior is unbiased or not.

2. Organizations can examine pay and promotion practices for design issues that make decision patterns more transparent while evaluations and awards are being made.

I can’t put my fingers on an old and useful study contrasting two methods of evaluating performers and the different effects on decision making, but… The study examined the evaluations of male and female managers, and varied whether the evaluations were made one at a time (i.e., single processing) or in groups (i.e., batch processing).

When people were evaluated one at a time, gender bias was demonstrated more often in the evaluation and reward decision. In contrast, when people were evaluated in groups, discrimination was significantly reduced. The researchers explained that in the ‘batch process’ scenario, decision-makers could actually see their gender bias in action (e.g., they could see that in 6 decisions out of 7, they were favoring the male over the female). In contrast, when decisions were made one at a time, decision managers forgot how often they rewarded a man over a woman. Batch processing might create a useful kind of real-time transparency, letting people see, evaluate and interrupt their own trend of bias.

3. Organizations can teach managers to be more mindful when they evaluate merit and rewards.

By mindful, I mean in the strictest sense, where ‘mindful’ is understood to as being not only active but also analytical about the way that they are processing information– but as seeking out and making novel distinctions. “Mindfulness is expressed in active (versus automatic) information processing, characterized by cognitive differentiation.” (Langer, 1989) What this means is that managers need triggers that interrupt automatic thinking and that force them to consider their decision criteria critically.

4. Organizations should investigate the degree to which they are actually meritocratic.

Do organizations that are actually meritocratic have managers that consistently make decisions that damage women and minority men? No. So organizations need to be transparent and hold themselves responsible for the effectiveness of programs intended to create a meritocratic organization. Organizations need to display their ‘diversity data’ internally (i.e., be transparent) and monitor to correct any patterns of bias (e.g., hold themselves responsible) in organization-wide decisions. They need to teach managers what it means to be meritocratic, and how to make decision based on merit while excluding irrelevant data. Organizations need to monitor the degree to which their claims of meritocracy map onto the outcomes of supposedly merit-based decisions.

The Paradox of Meritocracy shows that the link between an organization claiming to be a meritocracy and actually being a meritocracy contradicts reality.

Meritocracies hurt women because claims that decisions are based on merit can hide decisions that are gender-biased.

These claims of being non-sexist, non-racist, and non-discriminatory are not only false, but they can also increase bias by letting managers think that vigilance is not longer necessary.

The opposite is true —

Any organization claiming to be a meritocracy has to sustain and validate that claim by holding itself and its members accountable for unbiased, merit-based decisions, or risk being hypocritical and inauthentic.

See also:

Want More Women on Tech & TED Panels? Reject Meritocracy and Embrace Curation

References

Castilla, Emilio J., and Benard, Stephen. (2010). “The Paradox of Meritocracy in Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55: 543-576.

Monin, B. & Miller, D. T. (2001). Moral credentials and the expression of prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 33-43.

Bradley-Geist, J.C., King, E.B., Skorinko, J., Hebl, M.R., & McKenna, C. (2010). Moral credentialing by association: The importance of choice and relationship closeness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 1564-1575.

Kouchaki M, (2011). Vicarious moral licensing: the influence of others’ past moral actions on moral behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(4): 702-15.

Instead of summarizing the details of the three experimental studies that the authors used to test their hypotheses, I refer you to their article, which can currently be downloaded for free at Administrative Science Quarterly. If you struggle to access a copy, email me for details.

Also, this discussion focuses on gender-based discrimination because that’s what was directly tested in the study’s experiments. However, the logic holds for other forms of social prejudice, such as prejudices against people of a given race, sexual orientation, gender performance, physical ability, and so on, that have no actual effect on an individual’s performance.

Images:

— Figure 4, The Paradox of Meritocracy, with updated non-meritocratic condition vs. meritocratic condition, p. 566.

— Stephen Colbert, with his “Best Black friend” Alan, claims moral credentialing by association.

— Nerd Merit Badges from– you guessed it– Nerd Merit Badges

I am an organizational consultant, change advocate, and organizational identity/reputation scholar with a PhD in leadership & organizations. I research, write about, and consult with organizations on the relationships between organizational identity, actions, and purpose. I teach Technology Management, part-time, at Stevens Institute of Technology.

My current research focuses on how social technologies in the workplace can drive organizational change, generate meaning, and catalyze purpose. See the

I am an organizational consultant, change advocate, and organizational identity/reputation scholar with a PhD in leadership & organizations. I research, write about, and consult with organizations on the relationships between organizational identity, actions, and purpose. I teach Technology Management, part-time, at Stevens Institute of Technology.

My current research focuses on how social technologies in the workplace can drive organizational change, generate meaning, and catalyze purpose. See the

{ 3 comments }

As ever, a superb summary of an oft-ignored phenomenon. Thank you CV.

Jeremy & Susan, thanks for the encouragement! I’m glad you’re finding these sorts of posts useful. cvh

Thanks CV. Great post, shared and tweeted 🙂

Comments on this entry are closed.